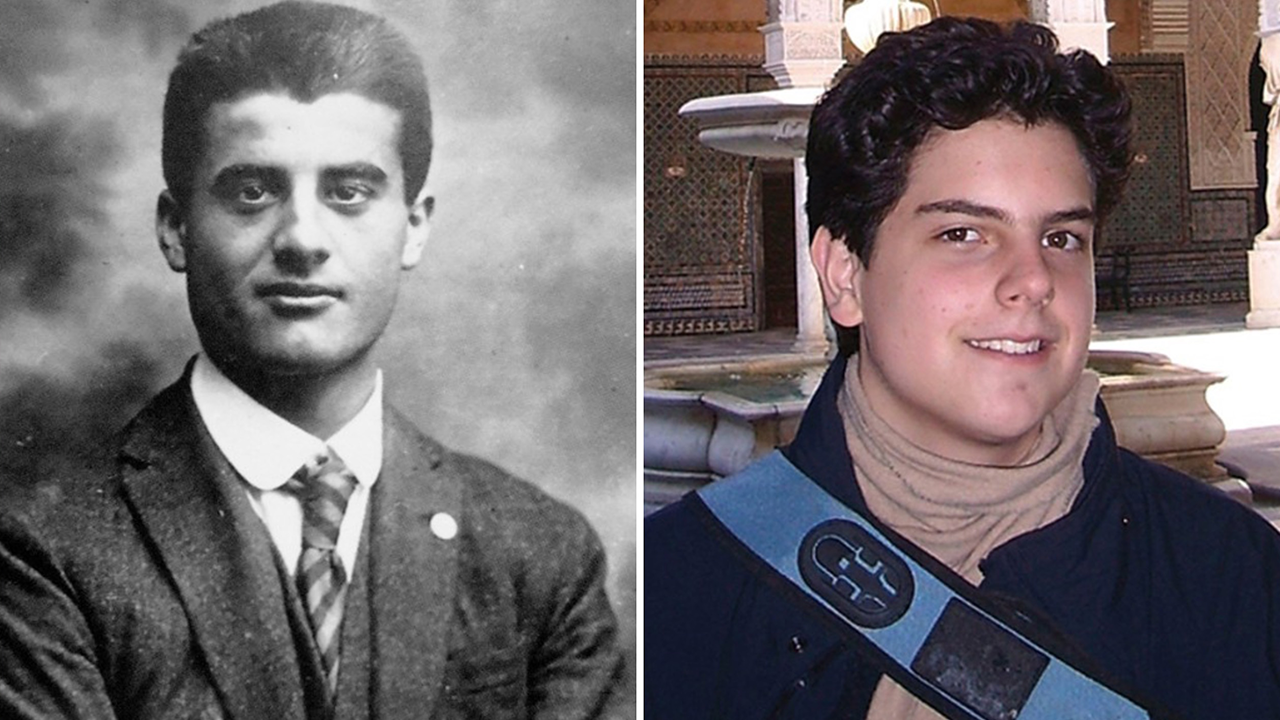

The picture above can be interpreted as the balancing act we each have. The feelings we associate with the heart and the reason we associate with the brain can become precarious. The routine of our lives has us choosing which to follow and which to ignore. This picture is an apt metaphor of how St. Thomas Aquinas described our rational soul. Per Aquinas, our rational soul has three complex powers. He describes them as intellect (reason, memory, calculation and understanding), the will (act, movement), and the passions (feelings, desires, emotions).

To Aquinas, the will is synonymous with act, our actions. Our will is not automatic or automated but blessed to be free, as in free will. There are bodily functions and actions that do not rely on our volition like breathing, heart rate, digestion, etc. Aquinas described these functions as different powers our soul in some ways shared with other living things. The other living things do not share the rational soul, that is, they are not self-aware. There is a great deal of classical, medieval, and modern thinking about our souls. The model used by Aquinas works well to help us understand the interplay between desire (passions) and reason (intellect). Particularly because they seem to be at odds with one another. St. Paul alludes to this quandary in his letter to the Romans, “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate” (Rom 7:15). We understand this struggle within each of us as an injury of the Fall. Our passions (the heart) and our intellect (the brain) are not aligned within us. They struggle to assert themselves and dominate our will, our actions. The Fall of Adam and Eve left us at odds within ourselves. This is called concupiscence or the predisposition to act contrary to what is good.

We often picture a devil on one shoulder and an angel on the other struggling to get a person to act in one way or another. The devil and angel image simplify this struggle too much. This image reduces the real struggle as between some perfect good and some terrible bad or evil. It is more helpful to think of our man on the tightrope. He demonstrates the act of will, that is, his movement toward his goal while balancing competing perceived goods. His passion for what he desires draws him forward and what he fears keeps him focused on what to avoid. At the same time, he learns, analyzes, and concludes rightness by reason. The true struggle is not between choosing what is bad or what is good. The struggle is between what we desire as a good and what we know to be a good. These may not be the same and sometimes they can be very different things. Our passions and our intellect seek what is good and avoid what is bad or evil. This first principle of our nature is written on our hearts by our Creator. Yet, the desire to do good is sometimes at odds with the desire to feel good or avoid discomfort. “They [the faithful] show that what the law requires is written on their hearts, while their conscience also bears witness, and their conflicting thoughts accuse or perhaps excuse them” (Rom 2:15). Here we have the issue. We may want to avoid actions which bring unwelcomed consequences, even though it may be the right action to do. Conversely, we may arrive at a considered opinion for action that lacks compassion, empathy or even mercy. These are powerful and weighty decisions. In a manner of speaking, they can throw you off balance.

Our man on the tightrope demonstrates the balancing act between these two powers within us. While our thoughts and conclusions may be judged right, moral, correct or their opposite, passions cannot. Passions simply are, they offer no considered response. By reason, we may judge our passions as aligned with the good or not. This is demonstrated by the fact that our man does not merely stand balancing on the rope. He has a goal, a destination. Each decision he makes, each of his adjustments either aids or inhibits his progress to that destination. For us, our goal is to be with God and share in the Beatific Vision.

We may say that our intellect informs the will, and our passions direct the will. It is not one or the other, it is both. Just as the tightrope walker most progress forward in act, he must also balance desire and knowledge. The tightrope walker has skill, experience, and knowledge to help him succeed. What do we have to succeed? We are baptized in the Holy Spirit and freed from Original Sin. We are therefore free to do what is right. We contend with concupiscence and so must pray for guidance, inform our conscience with study, and participate in the sacramental life. What will keep us in balance? The regular reception of sacraments of Reconciliation and Holy Eucharist. Our passions are powerful, so is the Holy Spirit, our intellect is fallible, but the grace of God is not.

– Frank Miller

![CANTOS DE QUISQUEYA [Social Media].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60c791b62191a839c2435b6b/934a4f97-ddd7-43dc-bc22-cc1c383c4d03/CANTOS+DE+QUISQUEYA+%5BSocial+Media%5D.png)